Because incinerators are often preferable to landfills, authorities in the Tampa region seek to expand one of the state of Florida ten incinerators by using funding from the Inflation Reduction Act. Opponents claim the plants pose health concerns.

Tampa is discovering, like many other rapidly growing metropolises, that more people also mean more trash. Officials there are responding by embracing a strategy that is well-liked in Florida: set it on fire.

source : NBC NEWS

Jack Mariano, the commissioner of Pasco County, which is located directly north of Hillsborough County in Tampa, said that “any areas that are experiencing growth are going to find issues of capacity” for handling trash. “Everyone’s facing the same problem: where to put the trash?”

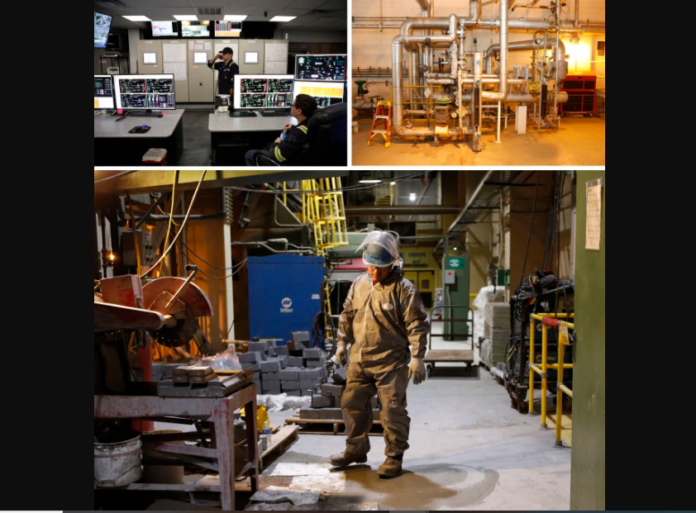

A $540 million plan to add a fourth boiler to the county’s waste-to-energy facility, or WTE, was approved by Pasco authorities in September. This would increase the incinerator complex’s capacity by approximately 50% and increase the amount of power fed into the electrical grid via a turbine that is spun by steam heated by burning garbage.

About $60 million of the project, which is expected to be finished in the summer of 2026, will be covered by money obtained via the Inflation Reduction Act, according to Mariano. The plant, one of three in the Tampa region that processes solid waste, can now process a third of the amount of garbage from Pinellas County to the west and less than two-thirds that of a neighboring Hillsborough WTE, according to a facility official.

Although WTEs have been in use for many years, studies by the US Environmental Protection Agency indicate that their technology is becoming safer and cleaner. Over the years, regulators have needed significant renovations, particularly to the 1989-built Pasco facility. A representative for the Energy Department said that many of the installations qualify for tax credits that were increased under the Inflation Reduction Act.

The director of solid waste and resource recovery for Pasco County, Justin Roessler, said that the incinerator there already had “rigorous air pollution controls” in place, such as the injection of activated carbon to filter dangerous gasses. Continuous monitoring of the site’s emissions is done to look for abnormalities, which are then reported to authorities.

According to a local official, part of the expansion proposal is equipping the boilers with modern technology to lower nitrogen oxide emissions. After everything is said and done, Roessler said, Pasco will be able to claim the distinction of being “the first waste-to-energy facility in the country to have a CO2 limit in its permit.” “We take great pride in that.”

Notwithstanding, waste-to-energy facilities manage very dangerous materials, and even the most environmentally friendly operations release amounts of harmful chemicals that are permitted by law when they burn. Residents’ worries about the possible health dangers have received more attention lately.

Last year, Ana Vale moved her family from Atlanta to a house in Doral, Florida, which is situated just 20 doors away from the incinerator for Miami-Dade County. Her now-14-year-old daughter started complaining of her skin burning and itching around two weeks after they moved there. She was given an eczema diagnosis by a dermatologist shortly after.

The factory then caught fire and burnt down on February 12, which added to Vale’s worries.

Despite newer studies connecting air pollution and other environmental pollutants to an increase in eczema cases, Vale claimed her daughter’s physician made no inferences about the incinerator’s influence. However, she thinks it plays a part.

She stated, “We lived in Atlanta for 12 years, and she never got that diagnosis—ever,” although she conceded that her access to doctors is restricted. We are a family of four. It becomes insane if we take them to the doctor every time they get ill.

Although some have, Vale has no intention of suing any government agencies or Covanta, the business that owns and operates seven of Florida’s ten WTEs, including Pasco’s.

Due to the Miami-Dade fire, a number of residents sued Covanta in March, claiming it had put them in danger of illness or had already caused them to get ill. In response to a complaint made by Earthjustice, a nonprofit that advocates for environmental causes, the EPA opened a civil rights investigation in June to determine whether state environmental regulators intentionally caused damage to the health of Black and Latino populations.

According to the Earthjustice case, authorities allegedly suppressed safety information on the emissions from trash incinerators in Florida from persons with disabilities or low English proficiency, and those groups are disproportionately more likely to reside close to the facilities.

An EPA spokesman said that the organization could not comment on ongoing investigations, even though it is not closely examining Covanta in this case. The Department of Environmental Protection in Florida chose not to respond.

According to Newsday, state environmental officials in New York are looking into claims that Covanta’s incinerator in Hempstead, Long Island, disposed of hazardous ash for years in a landfill close to a community that is mostly Black, with some residents alleging health effects. This month, a family filed a wrongful death case against the nearby school system, claiming that the plant was a factor in their son’s diagnosis of lymphoma when he started middle school there. That was a year ago.

The lawsuit does not identify Covanta, and the firm has denied any misconduct over its ash disposal methods, claiming that they were supervised by authorities and that there is no proof that has surfaced connecting its activities to any health risks.

Covanta area asset manager Patrick Walsh, who is in charge of the WTEs in Pasco, Hillsborough, and Lake counties in Florida, stated that it is simple to “point the finger at us” because the company’s incinerators frequently have “the tallest stack on that skyline in a very heavily industrial area.” Walsh further stated that further investigation is required to evaluate the health claims.

According to Joe Kilsheimer, executive director of the Florida WTE Coalition, which is made up of Covanta and a number of South Florida government agencies, “you have to compare waste-to-energy to the alternative.”

With the highest population increase in the nation last year, the state—which prides itself on being able to burn more municipal solid trash than any other—saw a massive influx of migrants to the Tampa area. Due to the high population along the coast, landfill space is costly and rare, since these sites release methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.

As the American economy weakens and people purchase fewer things and toss away less of them, waste volumes should normally decline, but Roessler said that “we have not seen that in Florida.”

Trash collectors collected roughly 51 million tons of trash in the state of California in 2022, compared to 47 million tons in 2020 – an increase equivalent to almost 90,000 completely filled semitrailers.

After serving as the head of the county’s sanitation department for 15 years, the chief retired five months after the Miami-Dade WTE fire. He left behind a warning to find a place to store all of the rubbish or to stop building work in the region to prevent waste from piling up.

A shortage is also present in Pasco County, where residential development is exceeding that of Hillsborough and Pinellas counties. According to Roessler, their WTE is already predicted to burn 440,000 tons of waste this year—nearly 100,000 more than typical. Additionally, home yearly trash disposal rates have increased to $100 from $93 last year due to the county’s population growth of 8% in the previous two years and a 15% increase in solid waste volumes in the last four.

According to Kilsheimer, at least six other WTE constructions or expansions are “actively considered” around South Florida. One such location is Broward County, which is home to Ft. Lauderdale and the state’s most ethnically diverse population. There, municipal solid waste volumes increased by about 13% between 2021 and the previous year.

A Covanta representative would only comment that “there’s a significant amount of interest in WTE in other markets in Florida than we are currently in,” without confirming whether the company intended to construct or run other plants in the state. However, opposition is beginning to seep in. Pembroke Pines homeowners in Broward crowded a town hall meeting in August to protest even the prospect of an incinerator being built nearby.

Supporters of the plants emphasize how the energy they produce powers nearby communities. According to the Pasco plant, it generates around 30 megawatts of energy per day, enough to power 17,000 households. It is anticipated that the expansion will increase that production by almost 50%.