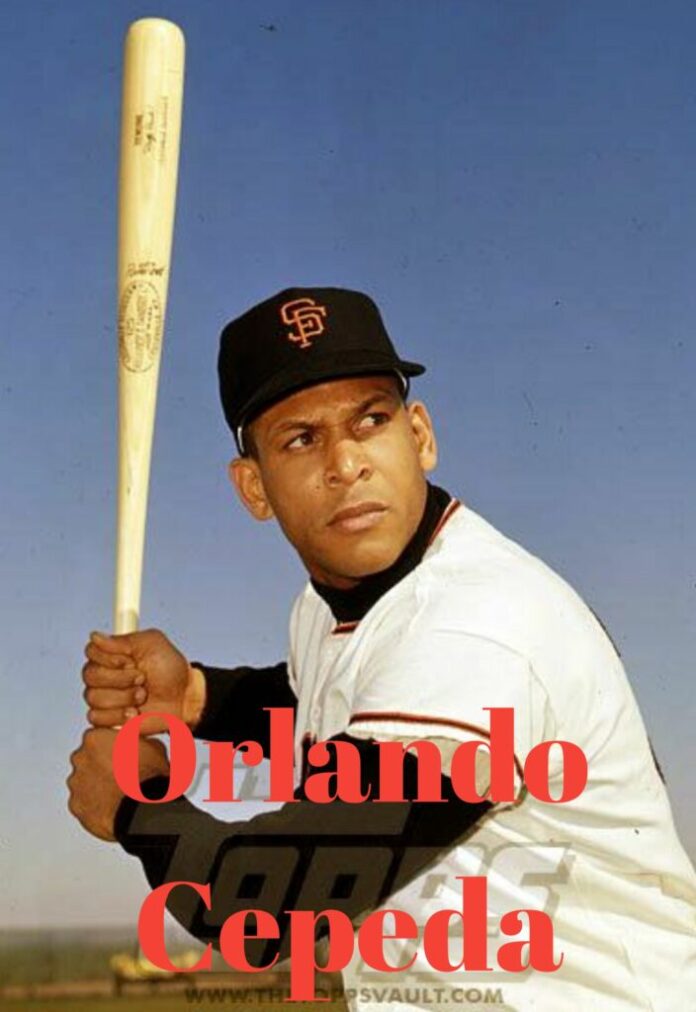

SAN FRANCISCO: Orlando Cepeda was one of the first Puerto Rican players to excel in the major leagues, a slugging first baseman known by the moniker “Baby Bull” who went on to become a Hall of Famer. He passed away. He was eighty-six.

A moment of silence was observed as his picture appeared on the Oracle Park scoreboard halfway through a game against the Los Angeles Dodgers, following the San Francisco Giants and his family’s announcement of his passing on Friday night.

Orlando’s wife, Nydia, published a statement through the team stating, “Our beloved Orlando passed away peacefully at home this evening, listening to his favorite music and surrounded by his loved ones.” “We take comfort that he is at peace.”

Up until he experienced some health issues in 2017, Orlando Cepeda often attended Giants home games. After suffering a cardiac episode in February 2018, he was admitted to a hospital in the Bay Area.

He became Boston’s first designated hitter and attributes his time as a DH with getting him inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1999 after being chosen by the Veteran’s Committee. He was one of the first Puerto Rican stars in the majors but was hindered by knee injuries.

“During his incredible playing career and later as one of the game’s enduring ambassadors, Orlando Cepeda’s unabashed love for baseball sparkled,” stated Hall of Fame Chairman Jane Forbes Clark. “We will miss his wonderful smile at Hall of Fame Weekend in Cooperstown, where his spirit will shine forever, and we extend our deepest sympathies to the Orlando Cepeda family.”

Orlando Cepeda, who was unemployed at the time, immediately agreed to be the Red Sox’s first designated hitter when they phoned him in December 1972.

In 2013, during the 40th year of the DH, Orlando Cepeda said, “Boston called and asked me if I was interested in being the DH, and I said yes.” “I made the Hall of Fame thanks to the DH. I’m in the Hall of Fame because of the rule.”

“I didn’t know anything about the DH,” he admitted, not knowing what it would imply for his career. For Orlando Cepeda , who participated in 142 games that season—the second-to-last in a stellar 17-year major league career—the experiment proved to be a great success. Just a few months had passed since the A’s acquired Cepeda from Atlanta on June 29, 1972.

On May 8, 2013, Orlando Cepeda was honored at Fenway Park at a ceremony honoring his position as designated hitter. His former Giants team was celebrating the defending World Series champions at the same time as the Red Sox had extended an invitation to him for their first home series of the season.

Back then, Cepeda stated, “It means a lot.” “Wow. Things are just getting started, even when you believe they are done.”

He alleged that Charlie Finley, then-owner of A, sent him a telegram warning him to call within twenty-four hours or risk being let go. Orlando Cepeda was fired in December 1972 for missing the deadline. After being acquired by Oakland in exchange for pitcher Denny McLain, he only appeared in three games for the A’s. Orlando Cepeda left knee ailment led to his placement on the disabled list. He missed four years of action due to ten total knee surgeries.

Prior to being included in the first group of baseball players to be designated hitters under the new American League regulation, Orlando Cepeda played first base and outfield.

“They were talking about only doing it for three years,” he explained. “And the concept of the DH is still unpopular with people. They predicted it wouldn’t endure.

Players like Orlando Cepeda and others from his period, who could still contribute at the plate in their later years but could no longer play the field with the precise defense of their primes, had fresh chances when the DH was added.

Orlando Cepeda was overjoyed to be given another opportunity.

After a stellar April with a.333 average and five home runs, he finished 1973 with a.289 batting average, 20 home runs, and 86 RBIs. August saw him drive in 23 runs in route to winning DH of the Year. At Kansas City on August 8, Orlando Cepeda hit four doubles.

“That was one of my best years,” Orlando Cepeda said, “hitting.289 with one leg while playing.” In a single game, I also hit four doubles. In addition to being the year’s designated hitter, both of my knees hurt.”

In the race for top D.H., Orlando Cepeda defeated Tony Oliva of Minnesota (.291, 16 HRs, 92 RBIs) and Tommy Davis of Baltimore (.306, seven home runs, 89 RBIs).

“It wasn’t an easy feat for me to accomplish,” Orlando Cepeda stated. “They had some great years.”

When Orlando Cepeda joined the minor leagues in the middle of the 1950s, he was one of the first Spanish-speaking athletes thrust into a foreign culture in order to play professional baseball, start a new life, and send money home. Cepeda also spoke little English.

If he could overcome difficult obstacles off the field, it was a chance for him to excel in a sport he loved.

A manager advised Orlando Cepeda early on to return home to Puerto Rico and pick up English before continuing with his career in the United States.

“Everything was a novelty to me, a surprise coming here my first year,” Orlando Cepeda recollected in a 2014 AP interview. “After a month of moving to Virginia, my father passed away. The day before I played in my first game in Virginia, my father passed away, saying, “I want to see my son play professional ball.”

“From there I went to Puerto Rico and when I came back here, I had to come back because we didn’t have no money and my mother said, ‘You’ve got to go back and send me money, we don’t have money to eat,'” he recalled.

Seeing so many young Latin American players come to the States with improved English language proficiency had continued to inspire Orlando Cepeda , in large part because all 30 major league organizations were emphasizing this kind of preparation through their academies in Venezuela and the Dominican Republic.

Young players can also take English classes through the various minor league levels and throughout spring training and extended spring.

He was not without problems.

Officers pulled Orlando Cepeda up for speeding in May 2007 and found cocaine in the car, leading them to arrest him.

Along with marijuana and a syringe, the California Highway Patrol officer detained Orlando Cepeda after discovering a “usable” amount of a white-powder drug that was probably either cocaine or methamphetamine.

Following the conclusion of his playing career, Orlando Cepeda was found guilty of importing marijuana in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1976. He was given a five-year prison sentence.

The Baseball Writers’ Association of America most likely did not elect him to the Hall of Fame because of this conviction. In the end, Cepeda was chosen in 1999 by the Veterans Committee.

Throughout his 17 seasons in the major leagues, starting with the Giants, Orlando Cepeda played first base. He also visited Kansas City, Atlanta, Oakland, Boston, and St. Louis. The Cardinals traded Cepeda to the Braves in exchange for Joe Torre in the spring of 1969.

A three-time World Series participant and seven-time All-Star, Orlando Cepeda won the 1958 NL Rookie of the Year award with San Francisco and the 1967 NL MVP award with St. Louis, a team that was devastated to lose him in the deal that brought Torre to town. Cepeda led the NL in 1961 with 46 home runs and 142 RBIs. Over his career, Cepeda hit.297 and had 379 home runs.

Not until after the 1973 season as a DH did Orlando Cepeda have the opportunity to reflect on his accomplishments and the significant role he played in history and the evolution of the game.

He said, “I just did it,” in reference to picking up the DH. “Every day, I say to myself, how lucky I am to be born with the skills to play ball.”

COLLECTED NEWS: NBC NEWS