Historically, viruses have been given names based on the hosts or animals in which they were initially found. Scientists are currently working to organize the disarray surrounding viral names.

Physicians started documenting global epidemics of a newly discovered infectious disease in the last decades of the 16th century. “Break-bone fever” (also known as “quebranta huesos” in Latin America) was a disease that affected people in Philadelphia, Puerto Rico, Java, and Cairo. It was characterized by a fever and excruciating aches throughout the body.

Thirty years later, in 1801, the sickness struck María Luisa de Parma, the Queen of Spain at the time, during an outbreak in Madrid. The Queen listed some of her symptoms in a letter she sent while she was getting better, and she called the illness by a term that is perhaps more recognizable to us now: dengue.

“I’m feeling better, because it has been the cold in fashion, that they call dengue,” stated the writer. “Since yesterday I’ve had some blood, which is what is making me uncomfortable, and after talking some time the throat hurts.”

We now understand that the four closely related viruses that cause dengue fever belong to a group called flaviviruses. In tropical and subtropical areas of the world, specific mosquito species, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, are responsible for its spread. Anywhere these insects are naturally located, outbreaks have the potential to emerge and to impact huge populations of people. The World Health Organization (WHO) received reports of over 7.6 million dengue illnesses and 3,000 deaths in the first four months of 2024, which is a higher number than the 6.5 million cases recorded for the entire year 2023. The WHO’s global dengue surveillance system has registered 5,366 deaths and 9.6 million illnesses by the beginning of July 2024, the highest incidence on record. The WHO reported 7,300 dengue-related fatalities in 2023.

Over the past five years, there has been a sharp increase in the incidence of the disease. This can be attributed to warmer, wetter conditions brought about by climate change and the El Niño pattern, which have made it easier for the virus-carrying insects to travel to new places and accelerate the disease’s spread.

In 2024, the virus was discovered to be actively spreading in 90 countries, with 31 of those countries reporting higher-than-normal case counts. In June 2024, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a health advisory regarding the increased risk of dengue virus infections in the United States, with the Americas seeing the largest increase in cases.

However, the tale of how dengue gained its name provides some insight into the fascinating and frequently illogical realm of viral nomenclature. While some viruses get their names from the places or even the animals they were initially found in, many viruses get their names from their symptoms. Some have lost their etymology to the passage of time. With the rapid advancement of analytical tools, the list of known viruses is expanding quickly. As a result, researchers are working to bring some order out of the chaos by creating systematic naming schemes that facilitate the identification and classification of newly discovered viruses.

Although 14,690 viral species have been formally recognized as of right now, scientists are unsure of the exact number of viruses that are present in the planet. For instance, it is thought that 320,000 viruses are only found in mammals, yet 140,000 bacteriophages—a kind of virus that infects bacterial cells—were found in a recent investigation of the human stomach.

There are now about 270 viruses known to infect people, but the number is constantly rising due to the advent of new viruses that cause infectious diseases as Mpox, Zika, and Sars-CoV-2.

Although the name dengue’s exact origin is somewhat unclear, it has something to do with the symptoms. Individuals who have the infection experience painful and uncomfortable mobility because it feels like their muscles and bones are tightening up. According to one hypothesis, the name dengue may have come from the Spanish translation of the Swahili term for the illness, ki denga pepo, which denoted an unexpected invasion by a malevolent spirit. Alternatively, it might have originated from the way the disease is most usually spoken in the Caribbean (“dandy”), or from the Spanish word “dengeruo,” which refers to the stiff, uncoordinated stride of those who have the disease.

The latter seems like a fairly lighthearted way of characterizing a rather unpleasant illness.

The dengue virus is a member of the haemorrhagic fever virus family of viruses. Numerous diseases are carried by mosquito bites, a few by ticks, a few by other mammals like bats, and some even directly between people by contact with bodily fluids like blood. All of these result in symptoms such as fever, excruciating headaches, discomfort in the muscles and joints, vomiting, diarrhea, and bruises and bleeding in various parts of the body. While not everyone will experience symptoms, viral hemorrhagic fevers can be quite painful. These include viruses like the Nipah, Marburg, and Ebola, which are extremely unpleasant diseases with high mortality rates.

It’s interesting, though, how the viral haemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) got their moniker. Some, like dengue, originate from a depiction of the symptoms.

Another viral hemorrhagic fever transmitted by mosquitoes damages the liver and results in jaundice in its victims. It’s hardly shocking that people choose to refer to it as yellow fever. This brings up an issue with naming viruses based solely on their symptoms, though, as other illnesses frequently have these symptoms.

Jaundice, or yellowing of the skin, urine, and even the whites of the eyes, is a common side effect of liver infections. Hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E viruses are excellent examples; however, the Epstein-Barr virus, named for two scientists who identified it, virologist Yvonne Barr and pathologist Michael Epstein, also causes liver damage that can result in jaundice. It causes glandular fever. Rarely, especially in newborns, the rubella virus—which also causes German measles and gets its name from the Latin for “little red” due to the rash it causes in its victims—has also been linked to liver problems.

Some of the viruses with more intriguing names can actually link their names to descriptions of the symptoms they cause. Chikungunya, a crippling virus spread by mosquitoes that causes fever and excruciating joint pain, means “that which bends up” in Kimakonde, the local tongue of the region of Tanzania in East Africa where the illness was initially identified. The name alludes to the agonizing position that a lot of virus-infected people take. “Very painful weakening of joints” is how the Acholi dialect of Northern Uganda refers to O’nyong’nyong, a similar virus that causes symptoms that are almost identical to those of Chikungunya.

Next, there are viruses that indicate the location of their initial discovery. For example, the virus linked to Bolivian hemorrhagic fever is named Machupo Virus after a river in San Joaquin, Bolivia, near the site of the initial epidemic that was discovered in 1959.

However, a few viruses have even come to be named after two locations that are thousands of kilometers away. Early in 1967, a group of medical professionals and scientists operating in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo published information about a virus that had been causing unexplained viral hemorrhagic fever epidemics in the area since the 1950s. The distinguishing characteristics of a virus that caused tick-borne hemorrhagic fever symptoms, which had been circulating among Soviet military personnel in the Crimea peninsula since the 1940s, were published later in 1967 by a Russian virologist.

After more research revealed that the two viruses were identical, the illnesses were united under the umbrella term Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever (CCHF). In the first half of 2022, there was a significant virus outbreak in Iraq that resulted in 212 cases of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever and 27 fatalities. Concerns have also been raised that the illness might spread to other regions as a result of climate change allowing ticks carrying the virus to move farther north and into areas of Europe like France, Italy, Spain, and the Balkans.

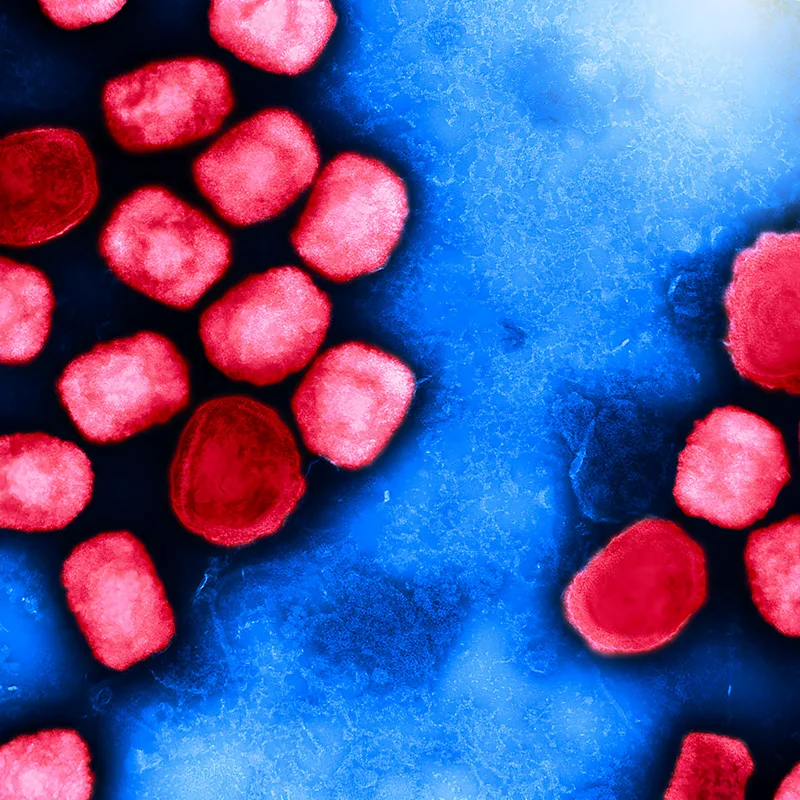

Additionally, the names given to viruses at the time of their discovery may be deceptive. A zoonosis, or animal illness that can spread to humans, is mpox. Up until 2022, it was known as monkeypox. However, the WHO suggested changing its name to mpox in an effort to stop the prejudice and stigma associated with the previous moniker.

Initially identified in monkeys brought to Europe for scientific purposes from Central Africa, the virus was initially called monkeypox. But the primates were unintentional hosts; rodents, such as the African rope squirrel, are the primary natural hosts.

Although the virus and smallpox (Orthopoxvirus) belong to the same taxonomic family, not all viruses bearing the word “pox” are related. Formally known as Varicella-zoster virus, the virus that causes chickenpox is actually related to the herpes simplex virus, which causes genital warts and cold sores.

Also Read : Frequency of asthma symptoms in children-childhood COVID-19 vaccination may reduce.

It is also unrelated to chickens. Instead, the common name comes from the blisters it produces, which resemble chickpeas somewhat (though other versions claim it was because youngsters with an infection looked like they had been prickled by chickens all over them). The word “zoster” means belt and alludes to the distinct bands of spots that patients with shingles encounter. The formal viral term “varicella” is derived from the Latin for spots, which are the huge pocks full of fluid and virus that are all over the body during chickenpox. However, during the last forty years, the formal identification process has progressed, and the official name of the virus has been altered to Varicellovirus humanalpha3, which sounds a little strange.

And this highlights how there has been a change in the way that viruses are named in recent years.

Although there may be a peculiar romantic attraction to naming viruses after locations or symptoms, this method of classification lacks the logic and structure that virologists require. To design diagnostic procedures and create antiviral medications, scientists must have a solid understanding of biological interactions. They can aid in developing vaccines and predict potential behaviors of newly emerging viruses.

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, an organization that keeps track of viruses with recognized names, has been prompted by this to look for more effective ways to bring order out of the chaos.

Thanks to developments in DNA sequencing technology, scientists can now determine the relationship between viruses and other viruses much more accurately. Certain viruses, for instance, can actually be the cause of very distinct symptoms than those that cause similar ones. Reexamining the viral haemorrhagic fevers reveals that four different viral families are potential culprits.

Their genetic composition determines how they are grouped together. Like many other living things, including bacteria, plants, and animals, you may be familiar with the entwined strands of DNA that are present within our own bodies—the well-known double helix. However, the world of viruses is much more complex. While some viruses can only have one double strand of DNA, others can have both.

Many viruses use an alternative genetic material called RNA, including those that cause severe diseases including flu, Covid-19, and viral hemorrhagic fevers. While some only carry one strand of RNA, others carry two.

These high-level genetic differences serve as the foundation for a classification scheme named for Caltech virologist David Baltimore, and they can be very useful in understanding interactions between viruses. Viruses in this system are classified into seven types according to the kind of genetic material they carry. It is very simple to identify viruses that use DNA for their genome: Group I viruses have double-stranded DNA, while Group II viruses have single-stranded DNA. Double-stranded RNA viruses belong to Group III.

Certain viruses possess a single strand of RNA that allows them to directly take control of the biological machinery infected cells utilize to transform genetic material into proteins. These comprise Group IV and are referred to as positive-sense RNA viruses. Others, referred to as negative-sense RNA viruses and making up Group V, require further cellular processing before their RNA code is ready for translation.

Two more classifications were established for complex viruses that do not fall into any of these primary classes. Group VI includes RNA viruses, such the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), whose life cycle includes the conversion of their genetic material into DNA. Group VII viruses, such as the hepatitis B virus, use double-stranded DNA, but one of the strands is incomplete, necessitating the synthesis of a segment of RNA along the way.

However, this is not the end of it. Let’s examine two viruses that cause symptoms that are similar in those they infect. Both the dengue virus and the chikungunya virus are positive sense RNA viruses, but a closer examination of their genetic codes reveals significant differences between them.

Virologists seek variances over similarities while attempting to identify a virus, say in a patient sample. Although useful, the category of all single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses is too wide. Thus, a different, complementary classification scheme is based on ideas that are comparable to the Linnean technique, so named for the Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus, which was created to categorize all living things.

The ICTV is used in this taxonomic scheme. It divides viruses into Orders, Families, and Realms. According to this approach, the Dengue virus and the Yellow Fever virus belong to the genus Flavivirus and family Flaviviridae. In contrast, Chikungunya is classified with O’nyong’nyong in the Togaviridae family and the Alphavirus genus.

As new knowledge becomes available, professional committees at the ICTV deliberate, evaluate, and revise the taxonomy of viruses. Name-related issues can also be resolved by the ICTV. An excellent illustration of this was the discovery in the middle of the 1980s that a novel virus was the source of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (Aids). The main research teams that isolated and characterized the virus suggested two possible names: Lymphadenopathy Virus (LAV) and Human T-Cell Lymphotropic Virus-III (HTLV-III). However, they were unable to come to a consensus, and nobody desired to make concessions. Consequently, the ICTV chose the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), which has been in use ever since.

But they have a tough task ahead of them. The number of viruses that are now known is increasing quickly due to next-generation genomic sequencing technologies. According to Peter Simmonds, a virology professor at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom and the chair of an ICTV subcommittee that discusses how to classify viruses, there were about 800 identified species of viruses five years ago. The number that is currently on the ICTV catalogue is getting close to fifteen thousand.

In addition to the official designations assigned by the ICTV’s taxonomy, the majority of viruses that are known to cause disease are typically given recognizable names. Its “role is in the way they are classified, although there is some overlap in the virologists who are doing the naming and the classifying” , Simmonds states. He notes that the novel coronavirus was given the name Sars-CoV-2 in 2019 by “an ICTV study group.”

Simmonds notes that given the rate of discovery, the total number of viruses that require classification in the ICTV taxonomy may soon surpass 100,000.

According to Jens Kuhn, lead virologist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Integrated Research Facility in Fort Detrick, Maryland, and an authority on the Ebola virus (another VHF), even this estimate may be conservative. Kuhn also chairs one of the ICTV subcommittees that deliberates the classification of viruses.

SOURCE : BBC NEWS