BY NBC NEWS

After eight months of looking for their 34-year-old son in Louisiana, his parents learned this summer that his body had been identified shortly after his disappearance and had been cremated without their consent.

When their 59-year-old brother was found dead from an overdose, his siblings in Michigan filed a missing person report after they were unable to get in touch with him. However, they claim that no one got in touch with them. His body was rendered completely unidentifiable after 514 days of storage at a county morgue.

It took a coroner in California more than three months to inform the man’s family after he passed away from complications related to COVID-19 and drug usage. The man’s brother quotes the coroner investigator as saying, “We dropped the ball.”

patchwork death notification Experts in death inquiry claim that these errors are avoidable. They assert that coroners and medical examiners ought to establish thorough written procedures for locating and getting in touch with next-of-kin. Experts advise officials to upload the names of the unclaimed dead to a government database so that families can look for their loved ones when all other attempts to locate them are unsuccessful.

However, an NBC News investigation has discovered that a significant number of coroners and medical examiners do not publish the names of the unclaimed deceased in the federal database, and others do not have formal next-of-kin communication processes in place.

patchwork death notification The cumulative result of these failings is that countless numbers of American families are left in the dark after a loved one passes away every year. Sometimes devastated family members actively look for loved ones who have already been buried or cremated for months or years in vain.

According to University of South Florida forensic anthropologist Erin Kimmerle, “the tools exist to solve many, if not most, of these cases.” “Having the will to do it is the key.”

Experts believe that tens of thousands of bodies go unclaimed each year in the country due to a variety of reasons, including financial hardships faced by the deceased’s family, the absence of surviving relatives, or a failure on the part of officials to locate or notify next of kin.

Finding families has become more challenging for officials in an era of widespread opioid addiction, soaring homelessness, and increasingly broken households. In many cases, the unclaimed dead were homeless or suffering from relationship-shattering addictions.

patchwork death notification However, in other cases, the authorities just don’t follow the right procedures to get in touch with family members.

In a number of incidents that were made public by NBC News this year, the Hinds County coroner buried victims in a pauper’s grave without telling their relatives, drawing criticism from Jackson, Mississippi, officials.

patchwork death notification Bettersten Wade had been looking for her 37-year-old son, Dexter Wade, for months. This summer, she found out that he had been buried at a county jail farm without her knowledge, having been struck and murdered by a police cruiser less than an hour after leaving home.

In February, Marrio Moore, 40, was brutally murdered in Jackson and laid to rest in a pauper’s grave on the same day that Dexter Wade was interred. Eight months after Moore was killed, his family discovered his name on a local news website, which is how they found out about his passing.

patchwork death notification This month, an NBC News reporter broke the news of 39-year-old Jonathan Hankins’s death and burial in Hinds County to his mother, who had been searching for him for more than 18 months. The reporter had obtained a list of unclaimed bodies buried in the pauper’s cemetery and cross-checked the names with a database of missing persons.

These issues affect the entire nation. From small towns to large metropolises, NBC News found instances in twelve states where families had to wait months or even years to find out about the death of a loved one.

patchwork death notification When a loved one’s body is unclaimed, family can be notified by the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, or NamUs, a free federal program. Every entry on NamUs is searchable on Google, unlike other government databases like the National Crime Information Center, which is only available to law enforcement. Anyone can view listings of people who have gone missing or who have not been claimed.

The system has shown to be successful. Of the over 20,000 unclaimed person reports added to the system over the past ten years, roughly 3,800 were later archived, according to data provided by NamUs. This means that in almost 1 in 5 cases, someone came forward to claim the remains.

Experts stated that the obvious conclusion is that each year, thousands of families across the country might receive closure by the straightforward act of publishing the names of the unclaimed dead.

But these names aren’t made public in large parts of the nation, including Mississippi.

patchwork death notificationAccording to Michelle Clark, a death investigator with Connecticut’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, which has a policy of listing every unclaimed body in NamUs, “it’s very sad that a lot of other medical examiner offices aren’t using it.” “Even if we are unable to locate family in Connecticut, we all have relatives who live elsewhere. As a result, occasionally a visitor from out of state will say, “Oh my gosh, that’s my cousin who passed away.”

It is optional to post to the unclaimed body database. An NBC News analysis of state statutes found that while at least 16 states have passed legislation forcing police and coroners to post cases of unexplained bodies and missing persons on NamUs, none of them specifically mandate the posting of unclaimed persons who have been identified.

An NBC News review of government data shows that during the previous five years, not a single active unclaimed person case was reported in NamUs in 90% of counties nationwide, including most of those with populations exceeding 200,000.

Numerous families have come forward to claim the remains of estranged loved ones as a result of local journalists’ attempts to fill in these gaps in a few locations, such as the suburbs of Philadelphia and Oregon, by obtaining the names of the unclaimed dead kept by local coroners and publishing their own searchable databases.

The family of 57-year-old William Swanton in Rhode Island, which has no cases listed in NamUs, didn’t find out he passed away and was buried in a city cemetery until 46 days later. This was despite the fact that Swanton’s public housing manager, the local police, and the county medical examiner all had access to the names and contact details of family members.

Later, the medical examiner’s office declared that law enforcement was in charge of getting in touch with the deceased’s next of kin. However, a police official stated that there was “nothing in policy” in the department regarding locating and informing families.

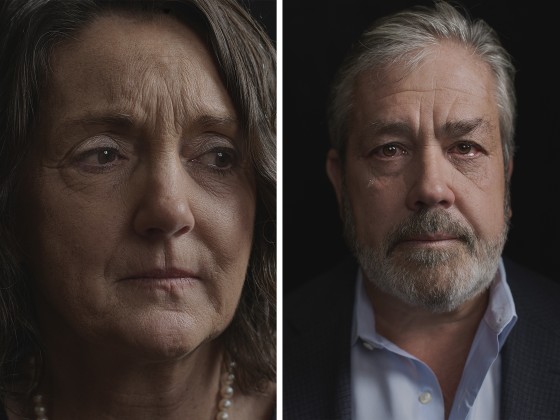

William Swanton’s ex-wife and mother of his two kids, Catherine Swanton, remarked, “Every step that could go wrong, it did go wrong.”

According to Kimmerle, the anthropologist from the University of South Florida, these misunderstandings and finger-pointing between police and coroners are alarmingly frequent in death notices, which is another reason why putting the names of unclaimed people on NamUs is a crucial safety measure.

“One group believes the other is taking care of everything, but nobody is actually taking care of anything,” the speaker stated.

“We would’ve located him.”

Sherry Pfantz made the decision to call the Orleans Parish Coroner’s Office in New Orleans once more on May 12, when she was heading home from work in southwest Louisiana. She wanted to know if they had her kid.

She was aware that these calls, which had turned into a somber aspect of her weekly schedule, were a gamble. Still, she had to give it a shot.

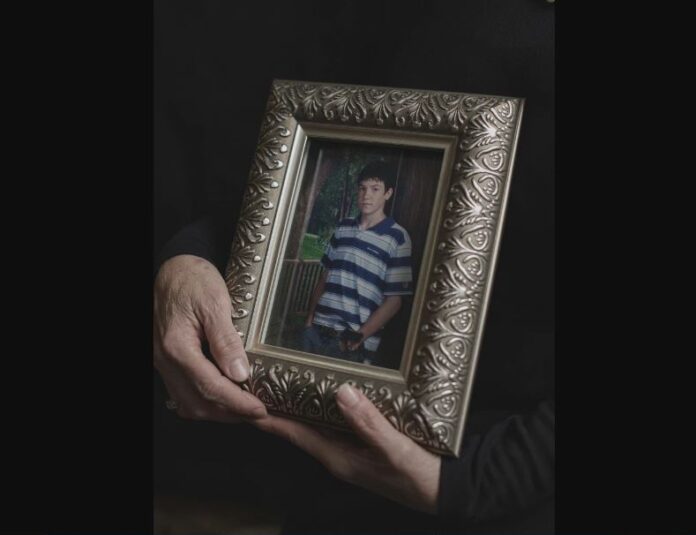

34-year-old Benjamin Pfantz had left a drug treatment center outside of New Orleans more than eight months prior. He had never gone more than two weeks without phoning, even while he was using. She and her husband had begun calling local morgues out of fear.

There was a wave of relief with every call. Her son may still be alive, but he was not present. But that afternoon, she remembered, the voice on the other end responded differently after Pfantz repeated his name and supplied his birthdate: “We have him.”

Pfantz had to veer to the side of the road to prevent a collision because the tears were coming down so quickly and violently. She claimed, through tears, to have heard two details from the coroner’s office employee that she couldn’t possibly believe.

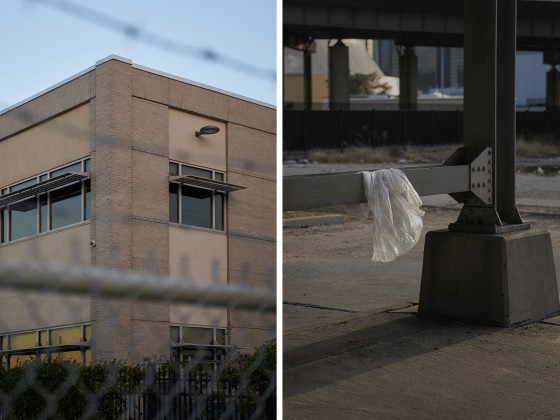

First, the mother stated that her son’s body had been received and identified by the coroner in September, just a few weeks after he had vanished and a few days after New Orleans police had discovered him unconscious under an overpass from an overdose. Moreover, the mother mentioned that her son’s remains had been cremated by the coroner months prior, so there would be no need to contact a funeral home.

Later, Pfantz remarked, “We never would have had him cremated.” “They deprived us of that option.”

She was baffled as to how this had occurred, as was her spouse, Theron Pfantz. They had exhausted every possibility to locate their son. They had reported missing persons to several Louisiana authorities, including Beauregard Parish, where they currently reside. They had driven four hours to New Orleans in order to look through homeless camps and hang posters, including Benjamin’s picture and their contact details. They kept cold-calling coroner’s offices, jails, and hospitals for months in the hopes of getting a lead.

Sherry Pfantz claims that she approached her son’s years of addiction with the same mindset she had while she was looking for him: “I told him I was never going to give up on him.” Furthermore, we never did.

Their health suffered throughout the months they were in the dark. Educator Pfantz stated that she typically maintained her composure during the entire day. But the moment she left the house, every day for months on end, the tears would come back.

On her way home, she found purpose and distraction from the grief when she called the coroner and other people. She now questions whether she and her husband would have found out about their son’s passing if she hadn’t kept calling.

The Pfantz family was later informed by an investigator from the Orleans Parish Coroner’s Office that the reason the agency withheld information regarding their son’s death was due to a clerical error; Benjamin’s last name, the investigator claimed, was spelled incorrectly in the coroner’s computer system.

That answer didn’t satisfy the pair. They claim that since both Benjamin L. Pfantz and the misspelled “Benjamin L. Peantz” had the same birthday, any sane person would have recognized them as being the same person. And why, after declining numerous times over the preceding eight months, had the coroner finally said yes in May?

They filed a complaint in August against Dwight McKenna, the coroner for Orleans Parish, claiming that his office’s “gross negligence” added to their son’s suffering.

Theron Pfantz stated, “The coroner had everything they needed to find us.” “They simply did not perform.”

NBC News sent written inquiries and requests for interviews, but McKenna’s office did not reply. The coroner’s office refuted any fault in the Pfantz case in a court filing.

patchwork death notification At a hearing in August, a member of the New Orleans City Council questioned McKenna about the issue. McKenna replied that his team makes a concerted effort to identify bodies and promptly contact relatives.

“I understand that everyone wants us to be able to quickly and easily identify their loved ones,” McKenna remarked, gesturing with his fingers. “It is not going to occur.”

In an attempt to avoid getting into the specifics of the Pfantz case, McKenna informed the City Council that occasionally his office just possesses “bad information.”

“Ultimately, our goal is to achieve accuracy, and to the best of my knowledge, we achieve this, albeit perhaps not as rapidly as we would like,” McKenna added. “I want to express my sympathies to the families of those who were affected. We just didn’t get it right in a timely manner.”

According to records examined by NBC News, an attorney for the Orleans Parish coroner stated that the office lacks established protocols or processes for identifying bodies or informing next of kin in response to a request for information from the Pfantz family’s counsel. Furthermore, an examination of federal data indicates that the coroner’s office, similar to all other coroner’s offices in Louisiana, does not upload the identities of unclaimed individuals to NamUs.

In addition, the coroner declined to provide the names of unclaimed persons buried or cremated by Orleans Parish since 2020 in response to an NBC News records request, stating that doing so “would require extensive, overly burdensome segregation of non-public records” and that there was no way to create such a list using the agency’s data management system.

According to experts, this prevents the public from finding out if there are any more people with unresolved missing person cases who could be included in the list of unclaimed deaths in New Orleans.

patchwork death notification The attorney for the Pfantz family, Richard Trahant, is also defending two other families who claim that this year, the Orleans Parish coroner neglected to inform them as well when a loved one passed away. He claimed that the examples demonstrate a startling lack of consideration for bereaved families, as does the coroner’s refusal to establish a procedure for identifying next-of-kin.

“Regardless of one’s religious convictions, how one treats the deceased is sacred to all,” Trahant declared. “These people are treating it like it’s a used burrito wrapper, while others spend years trying to find and return the bodies of missing loved ones.”

Sherry and Theron Pfantz claimed that during their months-long search, no one had brought up NamUs to them.

However, they are certain that they would have been able to return Benjamin home months sooner if the Orleans Parish coroner had entered his name into the system, even with the misspelling.

Theron Pfantz of NamUs stated, “We would have found him if his name was on that site.” “Because we never gave up searching.”

America’s patchwork death notificationCoroners need a while to adjust

The NamUs database only included two datasets for the first ten years after it was established in 2007 by the National Institute of Justice: unidentified bodies and missing persons. The intention was to develop a publicly accessible system that would enable law enforcement and relatives to make the connection between situations where a body could not be identified and inquiries into missing persons.

However, it took some time for National Institute of Justice officials to discover they were lacking a crucial component of the puzzle required to resolve many of these cases.

Coroners and medical examiners were successfully identifying bodies in tens of thousands of instances annually, but they were unable to locate the family members. As early as 2009, a few coroners had started entering the names of these unclaimed individuals into the NamUs database, which is used for unidentified bodies.

America’s patchwork death notification According to Chuck Heurich,a senior physical scientist at the National Institute of Justice and program manager for NamUs, the organization developed the third dataset especially for unclaimed bodies that have been identified roughly five years ago in an effort to urge more governments to record these cases.America’s patchwork death notification

America’s patchwork death notification Since then, according to Heurich, his team has toured the nation, giving speeches at conferences for national medical examiners and state coroners associations in an effort to promote the free system. Heurich said that while the unclaimed body database has proven to be useful, adoption has been sluggish in the absence of a national mandate or the adoption of uniform best practices among coroners.

America’s patchwork death notification “Every time we ask, ‘Who has heard of NamUs?’ at the beginning of a presentation, it never ceases to amaze me. Year after year, there are so few hands raised, and you just scratch your head, wondering what’s going on,” stated Heurich. “Because I think our outreach and training efforts are going pretty well.”

Heurich stated that even with the program’s general lack of use, NamUs’ ability to provide comfort to anxious family members is demonstrated by a number of case studies.America’s patchwork death notification

America’s patchwork death notification In one such case from the previous year, when Leford “LJ” Williams’ family went two weeks without hearing from him, they became concerned. Despite his battle with heroin addiction, Williams, 55, a resident of New York City, made sure to stay in constant communication with his three siblings.

America’s patchwork death notification They went to police stations, rehab facilities, and hospitals. They combed across parks and his former haunts.

However, they were unaware of the reality—that Williams had passed away 53 days earlier—until one of his nieces checked up on his name in the NamUs database in late April 2022.

His sister Geneva Gee recalled saying, “Oh, my God,” when her daughter showed her the online page and a picture of Williams’ corpse.America’s patchwork death notification

On March 1, Williams overdosed fatally in the East Village Starbucks restroom. Gee claimed that neither the hospital where he was pronounced dead nor the city authorities contacted any of his family members, despite the fact that his license contained his family’s address.

“It’s inhumane beyond words,” Gee remarked.

Williams’ family is currently suing the city and the hospital that treated him, claiming that they were illegally depriving them of the right to have “immediate possession” of his body as his heirs.

America’s patchwork death notification In court documents, the hospital, Mount Sinai Beth Israel, and the city refuted the accusations. The medical facility declined to respond. According to a statement released by the Office of Chief Medical Examiner in New York City, it “followed protocols in this case, including multiple attempts to contact the next of kin.”

With around 6,000 active cases (more than a third of all entries) in the NamUs unclaimed persons database, the office is by far the most frequent user of the database.America’s patchwork death notification

America’s patchwork death notification Gee expressed her gratitude for being able to locate her brother in the end, even though she believes there were obvious mistakes made in not informing family members of his passing.

She said, “Thank God for NamUs.gov.” “It ought to be required.”

“I need everyone’s assistance.”

According to Bill Yates, the chief deputy coroner for Jefferson County, Alabama, coroner’s offices are free to determine how much work to do in locating the relatives of unclaimed bodies in the absence of any state or federal mandates.America’s patchwork death notification

America’s patchwork death notification He claimed that his office in Birmingham goes through a rigorous procedure to locate a deceased person’s next of kin, looking through state driver’s license data, police reports, and hospital records to locate emergency contact information. Yates claimed he also uses paid people-finder services to locate addresses and phone numbers and combs through genealogy websites to reconstruct the deceased person’s family tree. Yates and his group also disclose the names of the unclaimed to NamUs and local media, in case they are still unsuccessful in finding family.

America’s patchwork death notification Yates stated, “I’m stating on NamUs that the Jefferson County Coroner’s Office has failed, and I need your help.” That is the way this office thinks. No, I do not wish to keep these names secret. I need everyone’s assistance.

Yates stated that 18 of the 180 names his agency shared with press and put to NamUs in recent years have had family members come forward. He explained that he and his team take this action because he feels that coroners have a moral obligation to provide families with closure and to prevent causing them more pain.America’s patchwork death notification

America’s patchwork death notification “When someone comes into contact with our office, it’s usually an unplanned death related to trauma or possibly an overdose,” Yates stated. “We want to relieve the family of that burden in any way we can.”

According to Yates, there is nothing preventing other coroners from taking up this mindset.

Still, family members look for deceased and identifiable loved ones for months or even years in case after case.America’s patchwork death notification

Last year, Malong Pendar received a call from an unknown number on the day after Christmas. It was a Santa Clara, California, Office of the Medical Examiner-Coroner investigator, and she had some very bad news. Njawa, his younger brother, had passed away.

When the worker informed Pendar that Njawa had passed away 108 days prior, his first amazement gave way to incredulity and finally fury.

America’s patchwork death notification “Why did he spend three and a half months just rotting in the coroner’s office?” Pendar stated in a conversation.

Pendar claimed he got a mute apology from an investigator in the medical examiner’s office when he later questioned them about why it took so long to tell the family. According to a complaint Pendar’s family filed against the Santa Clara County Medical Examiner-Coroner’s Office, the man apologized. “We lost the ball somewhere along the line.”

Njawa Pendar, 45, passed away from a heroin overdose that was made worse by Covid-19, as reported by the office of the medical examiner.

After his father passed away, he struggled with substance abuse and cut himself apart from his family.

Several relatives’ names would have come up in a Google search, according to Malong Pendar.

When Njawa’s family did eventually get his body, it had decayed so much that they were unable to embalm him and have a public funeral. Ultimately, his brothers said, it was not possible to bury him as they had wanted; instead, he had to be cremated.

America’s patchwork death notification Malong Pendar stated, “We’ve tried swallowing the pill, but it’s been horrible.”

Citing the ongoing dispute, a representative for the Santa Clara County Medical Examiner-Coroner’s Office declined to comment.

Like the majority of coroner’s offices in California, the county agency does not upload the names of the unclaimed deceased to NamUs.